Barry Lopez’s writing has been a major influence for me—I carried Arctic Dreams around for years, sharing passages and ideas from it with anyone who would listen. What impressed me so much about Barry’s writing, and Arctic Dreams in particular, was the slow-moving attention to detail. I felt like he was with me, using his version of a view camera—or I was with him—as he studied and thought about and tried to make sense of the world. —Virginia Beahan

From Here to the Horizon represents the gift of fifty American photographers—colleagues and friends and admirers—assembled to honor the life and influence of the writer Barry Lopez (1945-2020). It also marks the realization of Lopez’s long-held desire to create a photographic companion to Home Ground: A Guide to the American Landscape, the “reader’s dictionary” of our national geography he compiled with co-editor Debra Gwartney in 2006. Taking the entries in Home Ground as their points of departure, the artists selected the photographs in this collection as a kind of call and response of words and images reflecting a conversation between the camera and the American landscape that began over one hundred and fifty years ago.

Emmet Gowin, Alluvial Fan, Natural Drainage, near the Yuma Proving Ground and the Arizona-California Border, 1988 – Alluvial fan

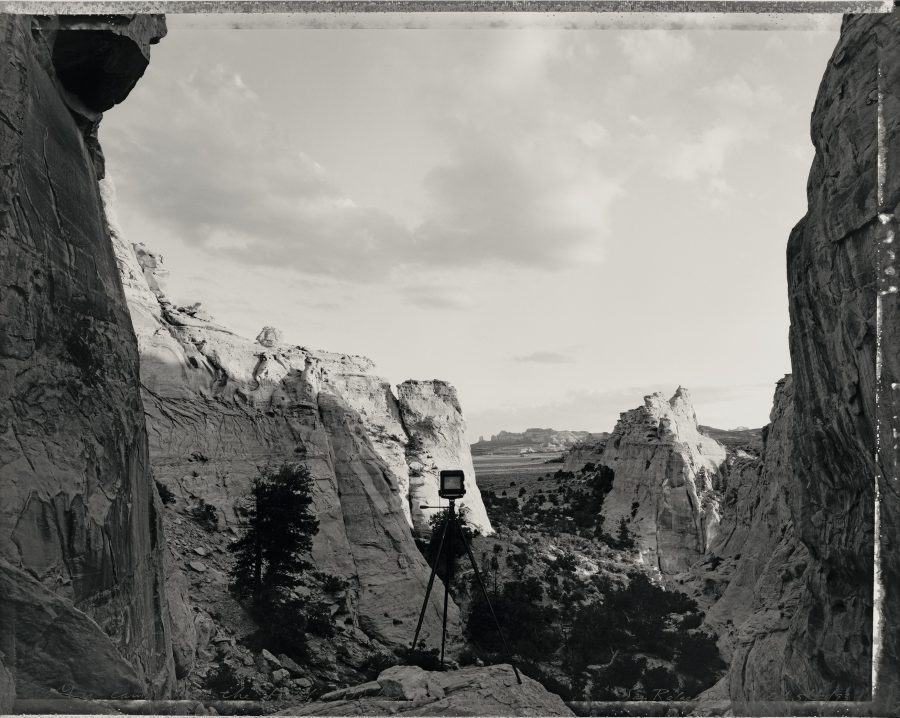

Some pairings are specific, an image depicting the exact location or landform as described in Home Ground—Lukas Felzmann’s foothill, Emmet Gowin’s alluvial fan, or William Sutton’s comb ridge. Others are more evocative—Allen Hess’s panorama of a bend in the Monongahela River places us in a lookout high above its banks, while we follow Peter de Lory on a hike through a slot canyon as he collects a trio of images of Utah redrock. An irrigation circle photographed by Andrew Moore draws from the Ogallala aquifer, which straddles the hundredth meridian—two vital landmarks that are nevertheless difficult to visualize on the ground. Likewise, Mary Peck asks us to imagine the boreal forest before it was cleared to make way for a tar sands refinery. These associations are by no means definitive, and many images relate to a number of possible entries—Thomas Joshua Cooper’s cauldron could just as easily stand for a channel, chute, or rapid incising the lava field of the Snake River Plain. Similarly, much can be found in a single vista—Steve Fitch’s animated jaguar overlooks the Tularosa Basin as well as the Oscura and San Andres Mountains, a Bureau of Land Management Wilderness Study Area, Holloman Air Force Base, White Sands National Monument, and the Trinity Site, where the first atomic bomb was detonated.

It has become a commonplace observation about American culture that we are a people groping for a renewed sense of place and community, that we want to be more meaningfully committed, less isolated. Many of us have come to wonder whether Modern American life, with its accelerated daily demands and its polarizing choices, isn’t indirectly undermining something foundational, something essential in our lives. …What many of us are hopeful of now, it seems, is being able to gain—or regain—a sense of allegiance with our chosen places, and along with that a sense of affirmation with our neighbors that the place we’ve chosen is beautiful, subtle, profound, worthy of our lives. —Barry Lopez, Home Ground

It is in the affection we have for our landscape that American photography discovered its character, speaking with a clarity and precision that reflects the boldness of its geography as well as its elegance and lyricism, even in places that might otherwise be considered ordinary or unremarkable. Landscape photography is foremost an art of topography, the objective description of a specific site, depicted in a manner that appears to be both truthful and reliable. While contemporary photography has largely dispensed with the heroic and easily romantic, it still takes its formal cues from the beauty of the landscape. Lopez often wrote about authority of the land itself—its “factual testimony”—and the intentionality revealed by its form. At its most basic, a photograph can be thought of as a kind of direct report of visible facts, one that creates a sense of structure and order through the relationships composed within the frame. But the rise and fall of our topography, our rivers and canyons, meadows and valleys, the profile of our mountains against the horizon have always been seen as inspirational and redemptive. And a photograph can give us much to see all at once—the reflection of clouds above a flooded field; shadows bouncing along a picket fence; a braided stream intertwined like a fingerprint—moments that might otherwise have escaped notice had the camera not drawn them to our attention.

We employ domestic animals (hogback ridge), domestic equipment (kettle moraine), food (basket-of-eggs relief), furniture (looking-glass prairie), clothing (the aprons of a bajada), and, extensively ourselves: a neck of land, an arm of the sea, rock nipples, the toe of a slope, the mouth of a river, a finger drift, the shoulder of a road. We put a geometry to the land—backcountry, front range, high desert—and pick our patterns in it: pool and riffle, swale and rise, basin and range. We make it remote (north forty), vivid (bird-foot delta), and humorous (detroit riprap). It is a language that keeps us from slipping off into abstract space. —Barry Lopez, Home Ground

Photography has often been said to arrest the “decisive moment,” fixing the instant the shutter was depressed. A landscape photograph, however, often works in the opposite manner, capturing not only a few fractions of a second but a culmination of events—the relationship of topography, light, and weather at the time of its exposure as well as the physical and geologic mechanics that give a place its structure. It is difficult to sit beside a river and not believe it has intention, to trace its course and not imagine some kind of judgment at work. While it is tempting to anthropomorphize the physical world, assigning it a purposeful consciousness or narrative, there is also some truth to this idea—a river does think its way through the landscape, guided by gravity and geology as it writes its course. Likewise, the prints themselves reveal a range of possibilities: as a mirror of the land and its physical disposition; as a kind of mnemonic device, reminding us of its tactile and temporal presence; and as a reflection of the emotional resonance of a place and our experience within it.

Barbara Bosworth, Moon Rising, the Night the Bird was Singing, Carlisle, Massachusetts, 2006 – Meadow

To hear the unembodied call of a place, that numinous voice, one has to wait for it to speak through the harmony of its features—the soughing of the wind across it, its upward reach against a clear night sky, its fragrance after a rain. One must wait for the moment when the thing—the hill, the tarn, the lunette, the kiss tank, the caliche flat, the bajada—ceases to be a thing and becomes something that knows we are there. —Barry Lopez, Home Ground

Laura McPhee, Irrigator’s Tarp Directing Water, Fourth of July Creek Ranch, Custer County, Idaho, 2004 – Sawtooth

“We have a shapely language, American English,” Lopez reminded us. The same is true of our landscape, full of places that inspire palpable, physical pleasure, bordering on desire. Scanning the view while hiking or driving or gazing out the window during a flight, the land unfolds before us as we trace mountain ranges and watersheds and coastlines. The sharp strike of a ridge, a tumble of boulders piled at the base of a cliff or the weight of a reservoir bearing against a dam reveal the tension and anticipation within the land. Or it may be as simple as watching as evening descends over the Plains to a background of birdsong and the occasional truck shifting gears. Behind all of these photographs, there is delight in the way that light defines the land, pleasure found in its shape and contour, and the reassurance of images that offer us a faithful and perhaps revelatory account of what was discovered before the lens. Each was made with attention and care and the good fortune of knowing that there is no better way to understand where we live and who we are—our past and what is waiting over the horizon—than to be able to walk the landscape and discover the view. Beyond standing as a marker of the admiration and affection of Lopez’s peers, like a cairn of stones that guides us through the landscape, it is hoped that From Here to the Horizon will spark our imagination—for places we remember, or hope to one day visit, or may never see yet carry with us thanks to a carefully written verse or a well-made photograph.

All photographs collection of Sheldon Museum of Art, Sheldon Art Association, the Home Ground Collection: Gift of the artist in honor of Barry Lopez

Text adapted from the exhibition catalog, From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry Lopez, Toby Jurovics, ed., (Lincoln, NE and Santa Fe, NM: Sheldon Museum of Art and the Barry Lopez Foundation for Art & Environment, 2023).

Quotations by Barry Lopez from “Introduction,” in Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney, eds., Home Ground: A Guide to the American Landscape (San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Press, 2006, 2013).