We’re living in a defining moment, both politically and environmentally. By making photographs that propose something bigger than the human experience, I hope to provide some perspective and a sense of scale. There is nothing explicitly political or moralistic about this work, but it comes from an acute awareness of our perilous course as a species and the ever-mounting consequences of our arrogance and unchecked consumption. Through photographs of subjects that suggest change on a level that falls outside the limits of our perception, I aim to explore the overlap between beauty, awe, and pathos. By stepping back to look at the larger system in flux of which we are only a small part, I want to find my own pulse, as it were, and assert an appropriately scaled sense of being within a hierarchy of this system. —Ron Jude

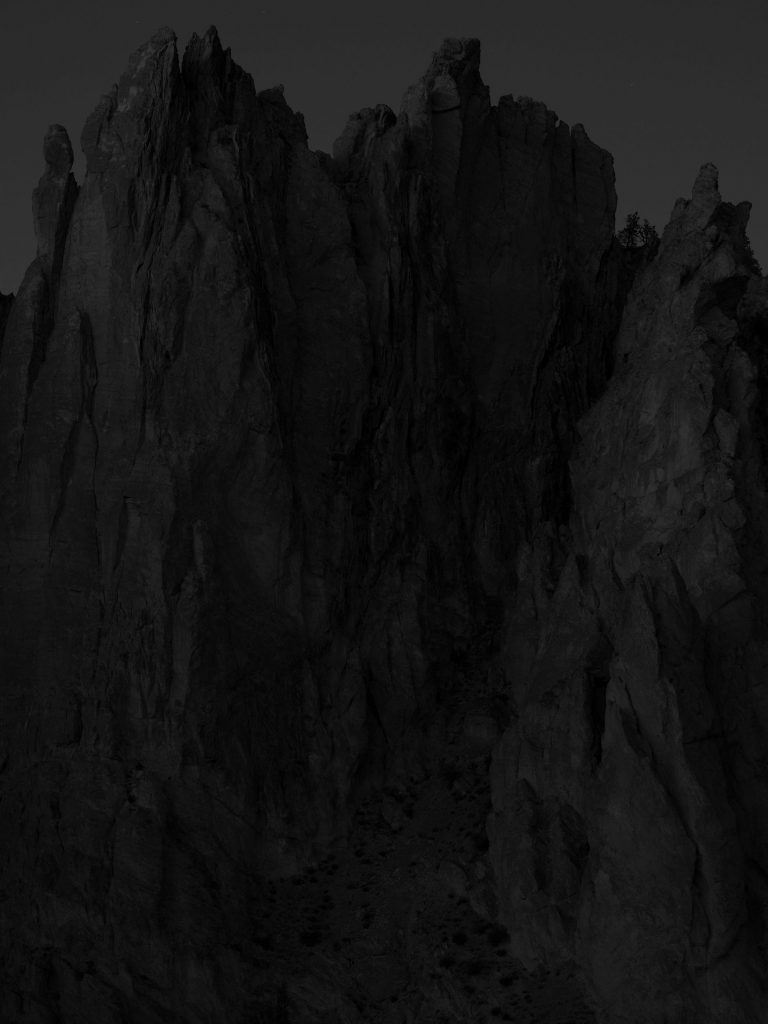

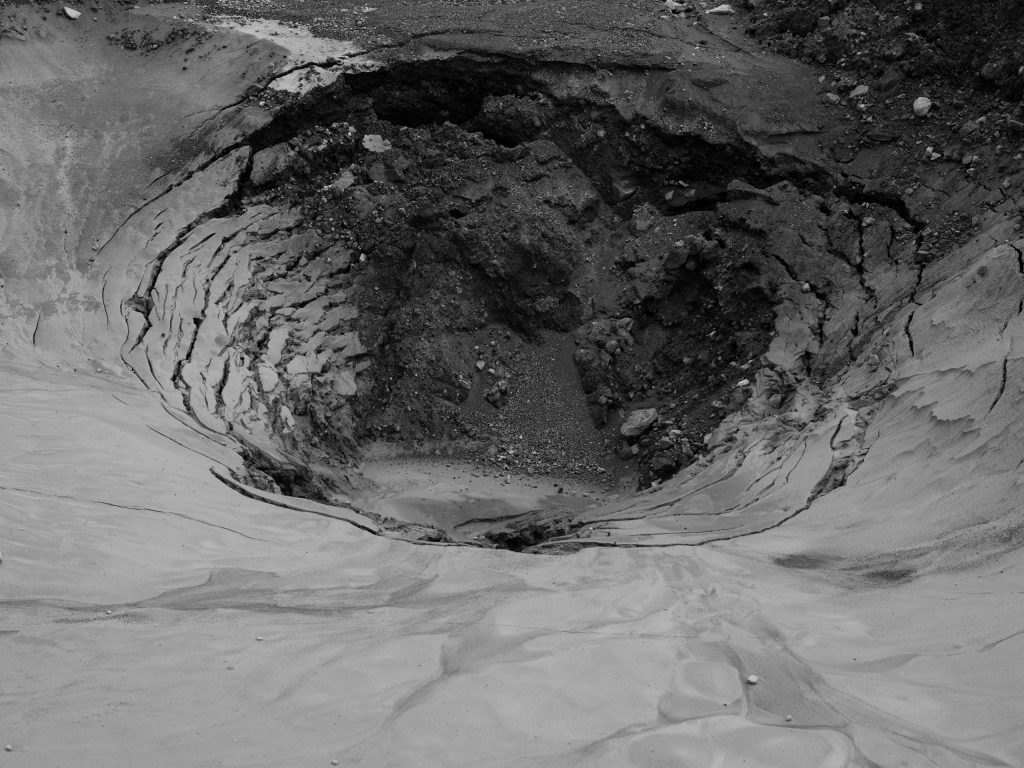

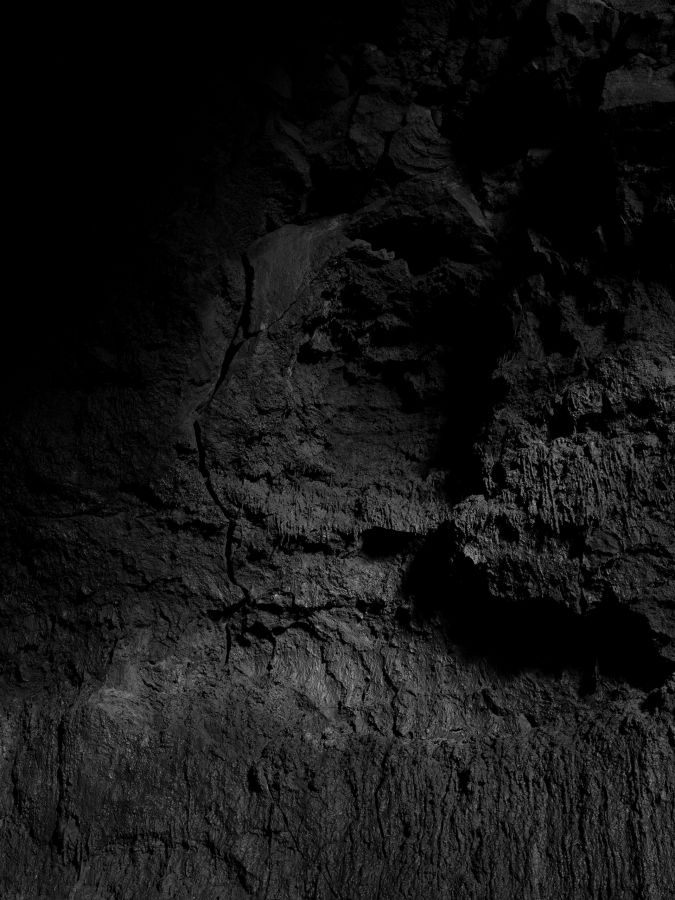

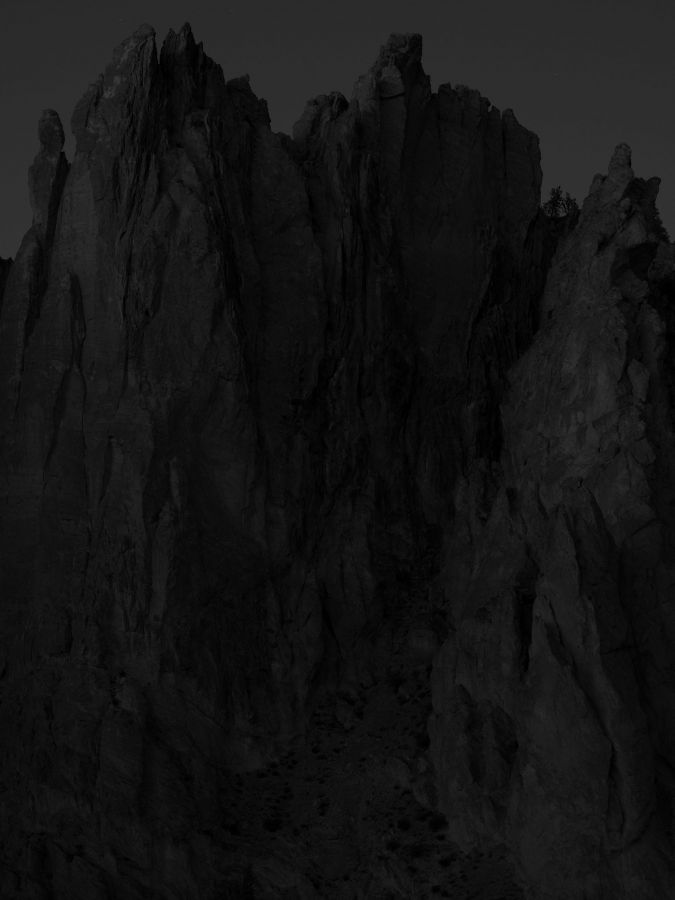

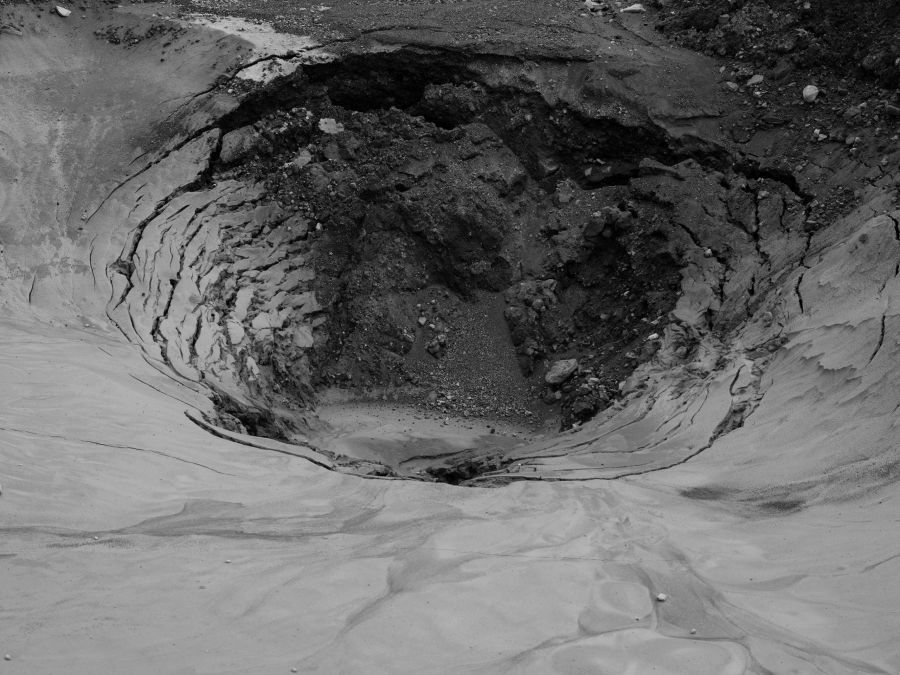

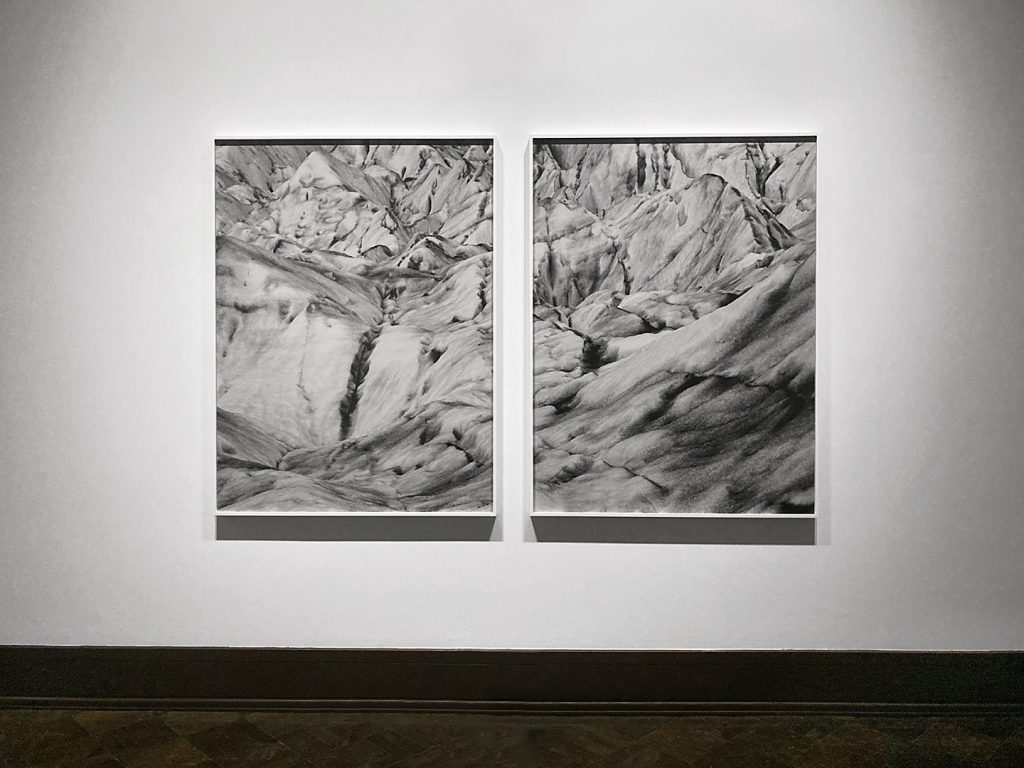

Ron Jude’s recent images defy customary expectations of landscape photography. Rejecting familiar narratives, their compositions are destabilizing and their subjects ambiguous, leaving us to question where they were made, where the viewer stands, and whether they are intended to suggest the past or the future. The series title 12 Hz – the lowest threshold of human hearing – references the limits of perception. Naming photographs after an invisible sonic property may seem counterintuitive, but just as we might strain to isolate a nearly undetectable tone, Jude’s images challenge us to consider other scales of time, motion, and light that exist at the boundaries of our awareness. Rather than picturing an idyllic wilderness or one comfortably domesticated, Jude explores what lies behind and beneath the landscape – the earth reduced to rock, ice, and lava, free of our imprint. His photographs arrest the forces and effects of gravity, erosion, tidal currents, and tectonic shifts that have shaped the physical world over millions of years.

In Jude’s earlier work, the landscape served as a background for human activity, a stage for unfolding narratives about memory and place. For this series, however, he discovered a subject close to his home in Eugene, Oregon, where the Pacific Ocean, the Cascade Range, and the lava fields of the high desert were all within a few hours’ drive. At Sahalie Falls on the McKenzie River, seventy miles east of Eugene (and a little over half an hour upriver from where Barry Lopez made his home), a forest service display highlights the region’s geology: “Lava, like water and ice, follows the path of least resistance. During the formation of the western Cascades, rivers, glaciers, and lava took turns shaping the landscape.” Jude became intrigued by the scale of geologic time made visible in the landscape and the intricacies of the earth’s systems, recognizing the rapids of the McKenzie River, the immense pressure of a mountain glacier, and the cooled surface of a lava flow as similarly in motion, albeit at vastly different rates.

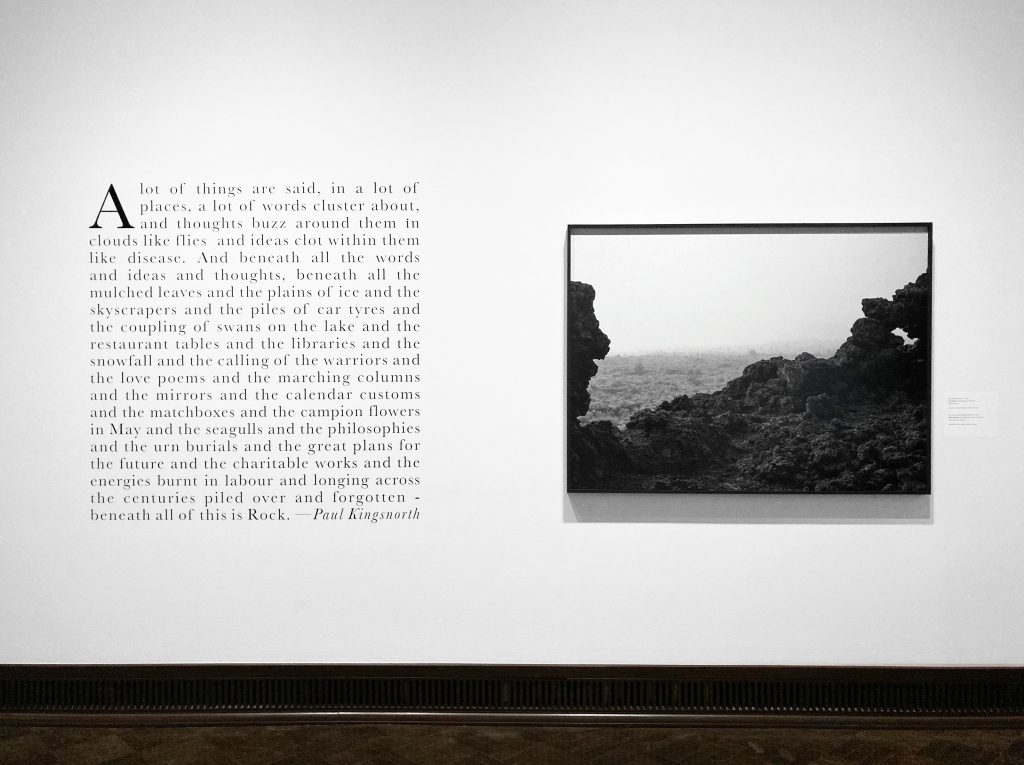

Over the next three years, Jude expanded his subjects to sites in California, New Mexico, Hawaii, and Iceland, although he declines to name or locate individual images. Visually, his photographs can appear almost impenetrable. Cliff faces and subterranean interiors shut out the horizon, while lava flows and glacial crevasses fill the frame from edge to edge. Scale and perspective shift from one print to the next. Images exposed underground or at night at first appear almost completely black, only to slowly emerge from the print surface. In these moments, Jude’s photographs become a surrogate for our own presence in the landscape, as we imagine unfamiliar terrain beneath our feet or feel our eyes as they adjust to the surrounding darkness. When allowed a glimpse of the horizon, its presence offers little relief. Scanning a jagged desert plain reveals a sky obscured by smoke, while overlooking a river as it plunges into a basalt cataract places us uncomfortably close to its brink. Only the sunlight seen through a rising veil of mist or its bright reflection off the surface of turbulent ocean waves offers a degree of hope, yet the effect is transient and ethereal.

Although his prints are visually luxurious, Jude is careful not to sentimentalize the landscape. They can feel inhospitable, and their scale threatening. However, to assert that the landscape is hostile or indifferent to our presence leads in a perilous direction, as it assigns a certain intention or agency to inanimate forces and anthropomorphizes the behavior of geologic systems. It is perhaps more accurate to suggest that the land operates independently of our actions and desires, over a timeframe that so far exceeds human experience it is difficult if not impossible to comprehend.

A lot of things are said, in a lot of places, a lot of words cluster about, and thoughts buzz around them in clouds like flies, and ideas clot within them like disease. And beneath all the words and ideas and thoughts, beneath all the mulched leaves and the plains of ice and the skyscrapers and the piles of car tyres and the coupling of swans on the lake and the restaurant tables and the libraries and the snowfall and the calling of the warriors and the love poems and the marching columns and the mirrors and the calendar customs and the matchboxes and the campion flowers in May and the seagulls and the philosophies and the urn burials and the great plans for the future and the charitable works and the energies burnt in labour and longing across the centuries piled over and forgotten – beneath all of this is Rock. —Paul Kingsnorth, author and co-founder of the Dark Mountain Project1

Ironically, however, while the planet’s systems are not tied to human endeavor, they are no longer unaffected by it. In only one example, recent predictions suggest Arctic summers could be free of sea ice in as few as fifteen years – an unimaginable pace when considered against the earth’s geologic timetable. More remarkably, the accelerating loss of glacial ice has caused a measurable shift in the earth’s axis. Although impossible to detect with the naked eye, its causes are readily visible. As we move further into the twenty-first century, Jude’s photographs may come to define a tipping point, marking an awareness of changes we have set in motion that are equally incomprehensible in their scale and consequence. He has said that his work is fundamentally apolitical – not an argument, but a reminder. But as we are forced to confront circumstances of our making that are reshaping the planet, and as more comforting images of the landscape begin to lose their meaning socially, politically, and personally, Ron Jude’s photographs may also offer solace in their record of the stoicism and persistence of the physical world.